Why does VR make my eyes hurt?

Virtual reality and augmented reality (VR/AR, collectively XR) technology seems to be in somewhat of a holding pattern. Even with everyone stuck inside thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic, there’s not been a run on VR headsets the same way there has been for toilet paper and trampolines. It’s not for lack of trying, but there are plenty of things the tech has yet to solve, both from a market perspective and from a technology perspective. VR/AR technology is expensive, it has a growing-but-still-limited amount of content, and the physical and computational requirements mean consumers have more to consider besides whether they want to play Final Soul Caliber Fantasy XXIV, DestinyTitanHalo 2, or Super Legend of Mario Multiverse Odyssey Quest.

![Has the Console Wars Gone Stagnant? [OPINION]](/img/console-tricolor.webp)

The market forces VR/AR has to contend with are challenging. Benedict Evans does a good job covering them in his latest essay. TL;DR? VR/AR has yet to “cross the chasm;” it is a technology for people who are into cutting-edge tech, and it has yet to convince the rest of us it’s more than a novelty. There is no Apple of VR (recent acquisitions notwithstanding); VR does not “just work.” Oculus, HTC, and the rest have come close, have taken the (Magic) leap, but no one has yet to land on the far side.

In this series I’m going to cover the various hurdles, technical and market-based, that VR and AR are still contending with. The problems are legion and aren’t going to go away overnight, but I do not for a second believe they are insurmountable.

First up: the vergence-accommodation effect.

The vergence-accomodation effect

Have you ever tried to pick something up in VR and hold it close to your face? The first time you do it, it’s hard to focus. Subsequent times seem fine, but you quickly start to feel odd. I feel vaguely unwell—not nauseous, though I know some people do—but just a general unpleasantness that’s hard to put into words. It doesn’t happen every time, but it gets worse when you throw things or look quickly back and forth between the foreground and the background.

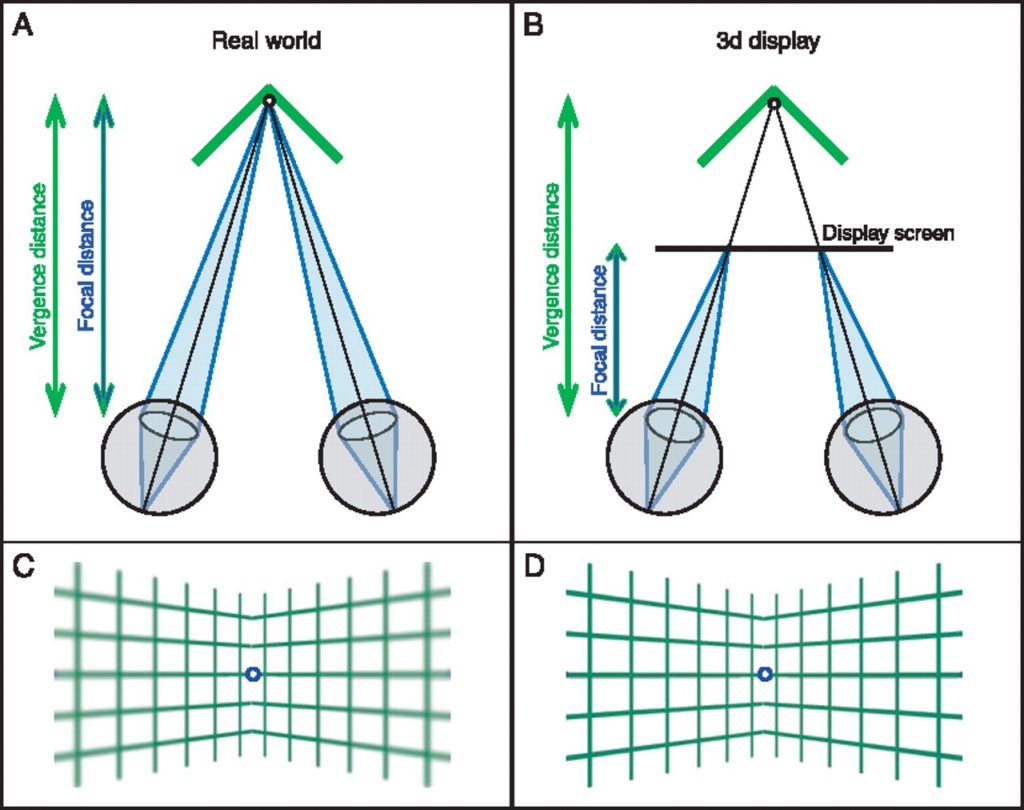

This is the vergence-accommodation effect (or vergence-accommodation conflict, VAC) at work. What’s happening? Let’s start with a picture:

Our eyes have evolved to allow us to control our focus (accommodation) independently of where we point our gaze (vergence). Your brain’s “software” adjusts them in tandem, usually as an unconscious reflex, which keeps whatever you’ve decided to look at in focus. This reflex can be consciously controlled; if you’ve ever successfully looked at a “magic eye” autostereogram, you’ve detached your vergence reflex from your accommodation reflex.

![[Stereogram+2.png]](/img/Stereogram%202.png)

Consciously controlling this reflex takes effort since we’re actively working against what our systems want to do. Your body wants to keep vergence and accommodation in sync so you can see properly, and it doesn’t like it when it detects you doing something counterproductive.

This is one of the main problems bedeviling VR and AR headsets. The main sets on the market right now all use a stereoscopic setup, where the user looks through two lenses focused at one point on a flat display. Thus, the user’s vergence distance is fixed in place.

There’s not an issue when looking at things in the distance, as the brain is… er… accommodating. The accommodation reflex automatically adjusts the focus, and has no problem dealing with a few degrees of separation from the vergence reflex. It’s a big issue when looking at something up close. Just as you start to develop a headache when staring at an autostereogram, you start to slowly develop a headache when looking at things up close in VR. The onset usually isn’t as dramatic, as your brain at least understands what it’s trying to do, but it doesn’t take long before it starts complaining, cutting short your virtual experience.

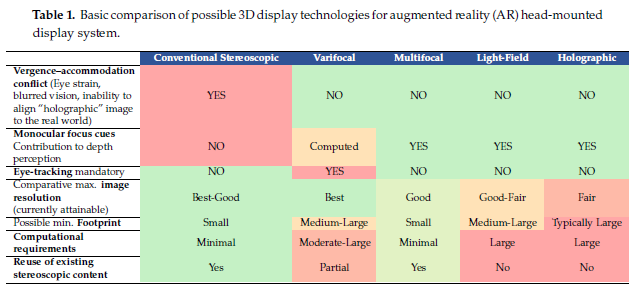

There are several promising avenues of research into solving the vergence-accommodation effect. Each has its upsides and downsides, but the general consensus is that stereoscopic headsets aren’t a long-term solution for VR, at least in the Ready Player One future that so many folks want to be a part of.

The main avenues receiving money and research energy are split between software solutions, optical solutions (varifocals, multifocals), and what I’m calling light solutions (light fields, holograms), which include taking advantages of the properties of light to actually “create” 3D visuals. While plenty of demos of each have surfaced throughout tradeshows and in research papers, none of them are ready for primetime.

I firmly believe that until the VAC is solved, widespread VR adoption just isn’t going to happen. The price tag of the gear, the content gap, the space and computational requirements are all real, but no one will willingly spend considerable amounts of time in an environment that makes their eyes water and their head hurt. That’s not to say there will be NO adoption. VR is here for games, some of which are frankly amazing. VR is here for medtech; doctors today are using VR to manipulate CAT scans and MRIs to get a better understanding of their patients. VR is here in design, architecture, real estate, and more. Yet it remains a niche in each category, a subset of a subset. VR is not yet here to the extent the hype machine claims, and it won’t be for a while yet.